The Admiration of the Black Female Body in press with Josephine Baker

Women pertain to a gender that is most of the time judged by its traits, nature, and physicality. In any part of the world, women face discrimination of all kinds, especially if they are part of a minority. In the United States of America, African-descendant individuals have endured a spectrum of injustices that have impacted their mental health, their personal lifestyle, and ultimately their perception of selves. Black women, whether they’re based in the USA or not, suffer the most, due to systemic racism and political-sociological dynamics.

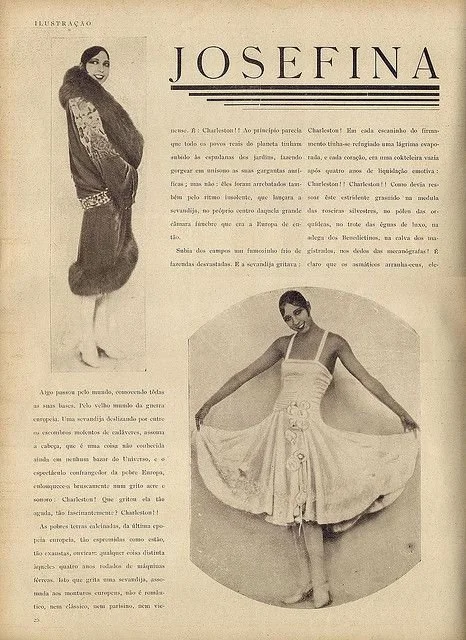

Image via Pinterest

In the introduction to “The African American Roots of Modernism: From Reconstruction to the Harlem Renaissance” by professor of African American Studies James Smethurst, the author highlights a sort of “general feeling that something happened in the expressive art of the United States in the early twentieth century that was different from what went before,” (Smethurst 2011). In fact, it is during the first two decades of the twentieth century that American Modernism started to take shape and form in its innovative endeavors and societal reflections. Black Americans in Modernism are usually associated with the illuminating Harlem Renaissance, a remarkable historical period in African American culture. In order to understand American Modernism as a whole concept, it is important to consider entertainment as a profitable and influential industry. Entertainment is shown in many different ways (Tv, live shows, movies, music, etc.) and its presence can be essential in many American people’s lives (McCann Worldgroup for MGM Resorts, 2017). What is showcased through entertainment has always played a big role in signifying a person’s traits, costumes, culture, and lifestyle. This happens a lot to Black women on stage.

Josephine Baker’s body and career displayed in the press

The Black female body encompasses two major dilemmas, which are related to race and gender issues. Their nature is in constant battle when it comes to portraying the right image of these bodies, especially in entertainment. Intersectionality plays a major role in comprehending any matter that is remotely related to the variety and complexities of the African Diaspora. I couldn’t think of a more complex, yet captivating figure like Josephine Baker, in order to analyze the representation in media, specifically in the press, of Black women in the entertainment industry.

The USA is a fairly new nation that was officially and politically founded in the second half of the 18th century. Just a century later, this country started its ascent towards a period of time that valued knowledge as an asset, materialism as an investment, and entrepreneurship as a means to accomplish anyone’s dreams: that was the century's embrace of Modernism. I’m personally fascinated by the work and the modus-operandi with which Josephine Baker exploded in the entertainment industry: a full-time creative, vibrant, and energetic soul.

Josephine Baker (1906 - 1975) is without any doubt one of the most important figures from American culture. The entertainment industry pays great gratitude to her today, through memorials, remembrances, and events dedicated to her. Dancers of all ages take Baker’s legacy into consideration when asked to name historical and meaningful impacts in the arts. However, Baker’s experience as a performer, both as a dancer and a singer, was highly and constantly scrutinized. It is no news that women in media experience gender and race discrimination more than their male counterparts. At the beginning of the last century, the press and media played a big role in portraying and promoting women’s reputation.

“She is still the toast of the continent and it has been said that she was the greatest drawing card in the old world”, states The Richmond Planet (run by African American editors in Richmond, VA) from 1930, while talking about Josephine Baker. “Josephine Baker took the famous "Charleston" and "Black Bottom" and made them the national dances of Europe.” On The Enterprise (run by Caucasian editors in Seattle, WA) from 1928, Baker is referred to as “The Celebrated Black Venus”, a title that enhances her natural beauty. “Miss Baker is splendid throughout with her frolicsome and original ways. Her dancing is much better than at the Follies, and she is by far the most natural person in the cast. Many other Negroes appear in the cast, and they, too, are very good, particularly in the native dances.” She’s also called by the same newspaper “pretty, well-formed, and wistful girl”.

To make things a bit quirkier, Ms. Baker was the owner of Chiquita (Chilton 2020), a pet cheetah that was supposedly adorned with a fabulous diamond-encrusted collar. She was also a spy for the French Resistance (McKay 2021) , and later in life, she adopted twelve kids from all over the world during the 1950s and 1960s (Denéchère 2021). She made sure to instruct them in their own native language, as well as their original tribes and heritages. The kids and Ms. Baker were all known in fact as the “rainbow tribe”.

It is noticeable that Josephine Baker was such an important figure in American History, a pillar in the African American community and any other minority groups. “Her live performances inspired numerous imitations, tributes and parodies by revistas and carnival troupes throughout the Southern Cone region”, writes Jason Borge.

She died in debt, leaving her charming residence at Les Milandes (in France) and “having to perform in several tours to keep her tribe” (Habel 2005). She was coherent with her principles until the end, remaining the truly new woman and new diva of Modernism and postcolonial France. In this research, the focus will be on the figure of Josephine Baker, how her dancing career was viewed, described, and appreciated around the world, and how critics and audiences reported her figure on paper. This study will also center on how an African American woman in the Modern era moved with her body and translated her femininity, activism, and civic duty to the press in different contexts around the globe.

The body and media presence of Josephine Baker

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the male gaze has been a major protagonist and element in American entertainment. The consequence of the male gaze, especially coming from Caucasian adult men, pushed a spectrum of stereotypes that would go from the “exotic” to “the other”, which Josephine paradoxically embraced and made a lucrative business out of it (Ruiz 2012). However, not everyone approved of her approach to empowering Black culture (Nardal 1928, cited in Musical Geography 2019). To her devoted readers, Martinique-born activist and writer Jane Nardal denounced in an article regarding Josephine Baker the dancer’s behaviors, accusing her to appeal to the White audience’s preferences by only serving them what they wanted to see and hear (Nardal 1928).

Josephine Baker lived and invented many personas, both on and off stage. Although her personality was perceived as a humble yet tenacious soul, Ms. Baker had to endure harsh criticism coming from the industry. The Jim Crow laws were in full effect at the time Ms. Baker’s career had sailed overseas, where she achieved most of her international success. The vaudeville circuit helped her escape from St. Louis, Missouri. A creative maelstrom was erupting in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance, and Ms. Baker wasn’t immune to its fascination. Nevertheless, at the age of 19, she was then offered the opportunity to join an all-Black revue show opening in Paris (La Revue du monde noir). She took the job and embarked on her intercontinental journey.

Europe at the time had a different relationship with Africa, compared with the United States and other countries. She disrupted the verticality and the hierarchical forms of European dancing and classical ballet. Through her mannerism, Ms. Baker was able to break into the European creative scene.

“We have to think of Josephine Baker as a symbol that the Jazz Age and the Harlem Renaissance could share that in some ways White and Black wings of this artistic movement that we could call Modernism could sort of meet in her as a symbol,” explains writer Darryl Pinckney in BBC documentary “Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar” (2009).

In this documentary, former dancer Brenda Dixon-Gottschild (The Black Dancing Body, 2005) pointed out that Ms. Baker displayed an innate attitude and never felt, or at least showcased, she was the victim of the stereotype of a Black woman, no matter how many fetishizations or predatory behaviors she may have been the subject of (Ruiz 2012).

Josephine Baker in Europe

When Ms. Baker arrived in Paris in 1925, two were the most famous scandalous moments that happened in her career: the Revue Nègre and the Danse de Sauvage, “in which a bare-breasted, feather-clad Baker danced a scintillating routing with a muscular, half-naked African dancer named Joe Alex” (Borge 2018).

On April 29th, 1929 The New York Times reported the story of a young man named Alexius Groh who stabbed himself to catch the attention of Josephine Baker (The New York Times). “He had followed the dancer from Budapest to Zagreb and besieged her with bouquets and love letters”, reads the article. A few weeks prior to this event, Ms. Baker’s performances were banned due to the imminent success and intriguing show she had given the days before. “Her semi-nude appearances aroused considerable public indignation”. No matter what she would do or say, men and women were in awe of Josephine Baker. Everything she would do and say would become a trend, but Ms. Baker had some testing times in Europe as well, where there were no Jim Crow laws, but there were political insurrections and racial prejudices all around. For example, in 1928 Viennese students banned Ms. Baker’s shows because their intent was not to have any negro performances playing in the Austrian capital. Her success started gaining much more traffic in the media only when she was already in Europe during the 1930s, but the American press had already set its eyes on the Midwestern performer. In Europe, she was known as the “darling of Paris” (The New York Times 1928), while still facing challenging audiences and comments from the local press. “When Josephine Baker arrived in Stockholm in the summer of 1928 as a star of the touring revue, Wien – Wien – Josephine, her fame preceded her arrival by at least a year.” (Habel 127).

The tour de France was also a major event where she gathered more attention from the press (McKay, 2021), with a three-year attendance (1933-1936) that saw many Italians and French people interacting with the African American dancer.

Overall, Ms. Baker’s time in Europe, beyond her years in France, pushed her to a stardom position, while also exposing her to a similar racial tension familiar with the United States. She was able to gracefully move within these fresh contexts for her, since the age of 19. Her visit to South America occurred a few years later her arrival in Europe, in 1929.

Josephine Baker in South America

Ms. Baker’s association with the Jazz Era made her more American rather than European, and this was not a favorable feature to the South American audience (Borge 2018). People in Latin America preferred European trends, especially coming from cities like Paris. When she embarked on her 1929 South American tour, she had a media reception from the press with mixed feelings: some reviews adored her, others diminished her explicit ways, not classical or puritan for the standards of the time. Differently from Europe, in South America Baker was capable to relate with a much broader audience of Afro-descendants, both in the audience and in the press. The Argentinian magazine Caras y Caretas published a study on her body and dancing movements (Borge 2018). Another Argentinian publication called Comoedia called Ms. Baker’s performances out, by addressing the observations with racist terminology. “All the emotive art of this epileptic negress is done with a monkey’s rhythm [for] she is a monkey on whom the modern hunter has placed a bunch of feathers in the same place where until yesterday she had a hairy, prehensile tale.”(cited in Seibel 2001: 202 from Borge 2018). By the end of the 1920s, the North American music genres and dance styles proper of the Harlem Renaissance had already made their international debut and fostered a general appreciation in each Latin American country (Borge 2018).

In the same year, Santiago’s Nascimento press published a translated version of Baker’s memoirs and music publisher Casa Amarilla showed her appreciation and positive reviews (Borge 2018). A series of letters from a group of conservative women were published on El Mercurio, where Ms. Baker was being judged as “sinful” and unworthy of praise. There was then the question of her androgenicity. Ms. Baker had in fact dark skin and a lean muscular body, which didn’t necessarily fit the fashion expectations of the times, especially in the Latin American environment. In the La Razón of Buenos Aires, they question her physicality:

“Is it a woman? Is it a man? [...] Her voice is piercing, shaken by an incessant tremor, mercurial, epileptic; her body twists like that of a reptile, or more exactly, it resembles a moving saxophone [...] Is she horrible? Is she charming? Is she black? Is she white? Does she have hair or is her scalp painted black? No one knows. There’s no time to tell. She comes as she goes, sudden as the sounds of a one-step [...] (Borge 2018).

In Brazil, the reception from journalists was almost the same. Certain publications more open to Avant-guard ideologies and afro-centric views, like Progresso and O Clarim da Alvorada, would write positively about Ms. Baker, but there were also a few journalists who condemned the dancer’s performance for the fear of being too disruptive to the local culture, which happened with short-story writer and journalist Orígenes Lessa (Borge 2018).

Conclusion

Josephine Baker signified the quintessential modern woman. During her life, she had to go through several harsh moments forged and orchestrated by the general public, due to racism and misogynistic mindsets. Nevertheless, the dynamism of this woman was able to highlight a few of the most important qualities that make an African American proud and independent through her craft and career. The journalists and business managers who shaped her persona hit all of her most prominent features, by being a woman in a Black body. The press did its secular job in reporting stories and facts describing the novelty of her artistic craft through dancing and singing, but not all of them were able to see beyond certain dogmatic prejudices. Despite the psychological pain Ms. Baker felt (Baker 1928, cited in Musical Geography 2019).

The way she handled international fame and her relationship with her own country are still admirable these days and a case to study while considering historical role models that served their community by operating in the show business, entertainment, and other similar creative industries.

An it girl, for sure. You can click on the image to get to the source.

This is an academic work. Here below is the bibliography:

Appel, Jacob M. "Baker, Josephine (1906–1975)." St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, edited by Thomas Riggs, 2nd ed., vol. 1, St. James Press, 2013, pp. 191-192. Gale eBooks,link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3404700392/GVRL?u=lehman_main&sid=bookmark-GV RL&xid=8373bb52. Accessed 17 Mar. 2022.

Blackening Europe: The African American Presence, edited by Heike Raphael-Hernandez, Taylor & Francis Group, 2003. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lehman-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1074959.

Borge, Jason. “The Portable Jazz Age: Josephine Baker's Tour of South American Cities (1929).” Urban Latin America: Images, Words, Flows and the Built Environment, edited by Bianca Freire-Medeiros, and Julia O'Donnell, Routledge (2018): n. pag. Print.

Chilton, Charlotte. “Josephine Baker's Life in Photos”. Harper’s Bazaar, 24 December 2020. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/celebrity/latest/g33562239/josephine-baker-life-in-photos/?sli de=17

HABEL, Ylva. “To Stockholm with Love: The Critical Reception of Josephine Baker, 1927- 35.” Film History: An International Journal, 17, 1 (2005): 125-138.

“Jane Nardal and Josephine Baker in La Revue Du Monde Noir.” Musical Geography, https://musicalgeography.org/jane-nardal-and-josephine-baker-in-la-revue-du-monde-noir/. (2019).

“Josephine Baker’s Dances Forbideen”. The New York Times, 14 April 1929, p.8. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1929/04/14/95923066.html?pageNumber=8. Accessed 15 May 2022.

“Josephine Baker’s Popularity Wanes In Paris, France”. The Enterprise, 4 October 1928, p.1 (frontpage).

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87093375/1928-10-04/ed-1/seq-1/#date1=1920&index= 19&rows=20&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&words=Baker+Body+body+Jose phine+show+Shows+shows&proxdistance=5&date2=1929&ortext=Josephine+Baker&proxtext= &phrasetext=show&andtext=body&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1&tab=tab_advanced_sear ch. Accessed 28 March 2022.

“Josephine Baker Star of the Film “Siren of Tropics”. The Enterprise, 17 February 1928, p.1 (frontpage).

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87093375/1928-02-17/ed-1/seq-1/#date1=1920&index= 6&date2=1929&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&words=Baker+interview+Josep hine&proxdistance=5&state=&rows=20&ortext=Josephine+Baker&proxtext=josephine+baker&p hrasetext=&andtext=interview&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1. Accessed 28 March 2022.

“Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar”. Written and directed by Sarah Broughton, narrated by Josette Simon, with Josephine Baker (archive footage), BBC, 2009.

McCann Truth Central Worldgroup. “The Truth About Entertainment Whitepaper”. MGM Resorts International, 2017.

McKay, Feargal. “When Josephine Baker Sprinkled Her Stardust on the Tour de France”, 14 October 2021, Accessed May 12 2022 https://www.podiumcafe.com/book-corner/2021/10/14/22643648/josephine-baker-tour-de-france

Ruiz, Maria Isabel Romero. “BLACK STATES OF DESIRE: JOSEPHINE BAKER, IDENTITY AND THE SEXUAL BLACK BODY.” Revista de Estudios Norteamericanos (REN) 16 (2012): 125–139. Print.

“Sensational Reception of Colored Stage Stars in Continental Capitals Dwarfs Miniature Success Achieved in United States!!”. The Richmond Planet, 15 November 1930, p.1 (frontpage) https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84025841/. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Smethurst, James. The African American Roots of Modernism: From Reconstruction to the Harlem Renaissance. The University of North Carolina Press, 2011. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/book/19262. Accessed May 13 2022.

“Stabs Himself Over Josephine Baker”. The New York Times, 30 April 1929, p.21. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1929/04/30/95938687.html?pageNumber=2 1. Accessed 15 May 2022.

“Siren of the Resistance: The Artistry and Espionage of Josephine Baker”. The National WWII Museum New Orleans. 1 February 2020.

“Vienna Bars Negro Dancer - Council Forbids Theatre to Permit Josephine Baker’s Appearance”. The New York Times, 4 February 1928, p.2. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1928/02/04/91469466.html?pageNumber=2. Accessed 15 May 2022.